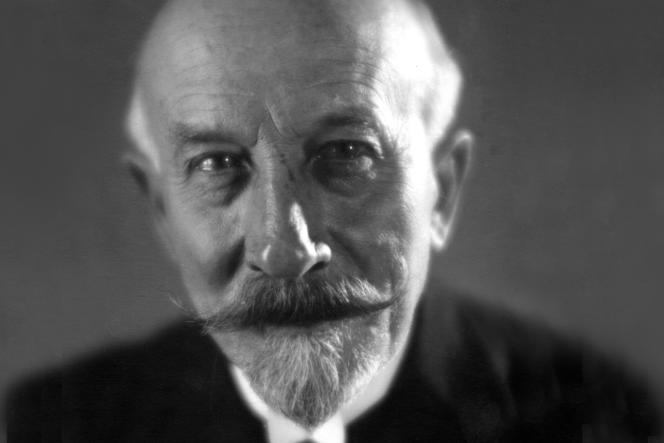

The X-Factor of Georges Méliès

Photo Courtesy of THE CANADIAN

The waning notion in which film of the contemporary age sulks in the brine of disparate — unicellular manifestation points is in need of discussion. Truthfully, when did cinema begin gaining notoriety as less of a form of monetary compensation and, conversely, as of an alcove for voyeuristic artists to dynamically refine their craft? I — for one — have still yet to gauge why the antithesis of this aforementioned question is so widely regurgitated. Although I do maintain an opinion, there are specific roots of “film” as an art-form. From the personal scope, it’s the cinematic achievements such as “A Trip to the Moon” and “The Kingdom of the Fairies” that make this topic rather enticing as well as indelibly didactic to debate. Each these of quoted works were from the subconscious of early twentieth-century silent-film maestro Georges Méliès. Mr. Méliès’ whimsical creations — while being embedded amongst the source material for modern expression pieces such as Martin Scorsese’s “Hugo” — emanate from a fresh leaf of pure, pedagogic enrichment.

His films develop from the perspective of a painting and finalize as moving rolls of film with a clouded silence. In essence, anyone can proceed to view the simplicities of directors such as Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin, yet the quintessential patient-zero of silent filmmaking still shines through as Georges Méliès. He repudiated the banal, edifying parameters of film and unceremoniously crafted his own blanketed oeuvre of artistic expression. He brushed aside the ingenious subtleties of cubistic artistry and fauvistic pop art and acted as a proponent for going against the grain.

A prime example of the ambition of Mr. Méliès is highlighted — arguably in its most unfettered tense — within his 1900 film “Joan of Arc.” And while preceding Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 take on the rather compressed tale of the heretic rebel’s bought with French nobles — which I consider to be one of the most conceptually flawless films ever conceived — the more pretensive and pre-modernist take on the narrative of Joan of Arc from Georges Méliès is quite divine. The 1900 edition occurs through the confines of a refined run-time of only eleven minutes. The film authoritatively incites its witty clutches upon the women’s tale with common usages of red to act as a combative force of devilish antagonism. And in consequence, the narrative’s alluring propensity absolutely blows me away. The immeasurable intrigue Mr. Méliès is able to incubate and release is simply another testament to his aesthetic mastery.